The joint success of Barbie and Oppenheimer means that movie theaters are thriving. The same cannot be said of theater etiquette.

Every day brings new moviegoing horror stories, like people taking flash photos or scrolling through TikTok during screenings. A viral clip from Brazil even shows two women getting in a fight as the Barbie credits roll, all because one of the women allowed her young child to watch YouTube videos at full volume throughout the film.

The rise of phone use in movie theaters has resulted in complaints across social media, and understandably so. Watching a movie in a theater is intended to be an immersive and communal experience. But one bright phone screen or blast of TikTok audio jolts us from that immersion entirely.

After all, in the words of Nicole Kidman, patron saint of AMC Theatres, "We come to this place for magic." We don't come to this place to stare at a stranger's flashlight-bright FYP in the dark.

SEE ALSO: The cult of Barbenheimer: In the pursuit of saving cinema, did we all lose our minds?Despite these valid complaints, some moviegoers remain hellbent on justifying phone use in theaters. Arguments range from "We paid for a ticket so we can do what we want" to "If a movie is three hours long, I'm going to get bored and take out my phone."

These reasonings devalue the communal moviegoing experience and place arbitrary limits on the films themselves. But more importantly, they also speak to how audiences' viewing habits have shifted over the years, thanks to elements like the rise of streaming and the commodification of entertainment as a means to viral fame.

Streaming and the second-screen experience have changed how we experience movies.

Streaming has made film and TV more accessible from the comfort of our homes — and as a result has radically altered the way we watch movies. One of these major changes is the rise of the second-screen experience, which is when you watch a movie on one screen, like a laptop or TV, while also interacting with a second, like a phone or tablet.

What can you do with that second screen? The options are limitless. You could research questions you have about a film, like who a certain actor is or what a bizarre scene may have meant. You could browse social media for reactions, text friends who are watching along, or just play Subway Surfers. The point is, you're engaging with two screens at once, and what's happening on the second screen isn't always connected to what you're watching on the first.

SEE ALSO: Barbenheimer shocker: What 'Barbie' and 'Oppenheimer' have in commonStreaming helped popularize the second-screen experience, and that popularity only increased as COVID-19 quarantining made at-home streaming the norm. As theaters closed and studios released blockbusters on streaming services and in theaters at the same time, audiences realized they didn't have to go to the theater to catch the most anticipated movies of the year. They could just catch flashy new releases like Black Widow or Godzilla vs. Kong at home.

Watching movies at home comes with a different social contract than watching them in public.Watching movies in this private environment comes with a different social contract than watching them in public. If you stream a movie with friends or family, the etiquette of home viewing allows for talking during the movie in a way that theater etiquette does not. The same goes for using a second screen to scroll social media or play a game. These behaviors aren't destructive to others' experiences when you're in this individualized context, but they are in poor taste once you make it to a theater. The theatrical experience is tailored to a large audience, not just one ticket holder.

Did COVID-19 quarantine routines ruin audiences for movie theaters?

Unfortunately, as audiences return to movie theaters following the end of strict COVID-19 public quarantines, they are having a hard time making that crucial distinction between the public and the private. With complaints (and memes) rolling in about people watching TikToks or texting during movie screenings, we're seeing how the second-screen experience is crashing into theatergoing — and how reluctant people are to break habits normalized by streaming.

I myself have witnessed an audience member reading the Wikipedia pages of the first three John Wick films during a screening of John Wick: Chapter 4. I've also seen someone texting their friends about how much they hated Beau Is Afraid — all throughout Beau Is Afraid. In both cases, my eyes were drawn to the brightness of their phone screens like a moth to a highly distracting flame.

SEE ALSO: 'Oppenheimer': Yes, there really was a nuclear reactor under a football field.There was a time when you'd reserve such research or reaction texts until after you'd left the theater, or at least until the credits had run. But a subset of today's audiences don't want to wait to get their thoughts out there or learn the answers to their questions. Instead, they're all too willing to break the social contract of movie theaters by treating them as a personal space instead of a communal one. This individualistic attitude is especially strange given the reign of Barbenheimer, which celebrates the very act of enjoying a movie with a rapt audience.

Moviegoing has become a quest for virality.

The Barbenheimer double feature is hands-down the biggest moviegoing event since COVID-19 quarantining shifted how studios release movies and how we watch them. Excitement for these films has translated from internet buzz into massive turnout in theaters. But Barbenheimer hasn't just provided film audiences with two great movies: It has also given them multiple paths to internet fame and notoriety. From memes to custom outfits, Barbenheimer is a viral phenomenon that moviegoers have flocked to in droves, hungry to claim a piece for themselves. Nowadays, it's not enough to just go see a movie; people need to know you've seen it, and the more people who know, the better.

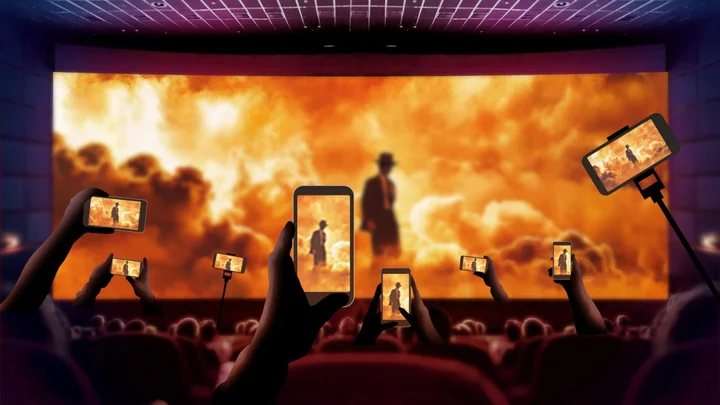

It's not enough to just go see a movie — people need to know you've seen it.Among these viral moviegoing trends is the practice of of taking photos or videos of the film as it plays. These photos and clips go beyond piracy, instead mimicking the kind of clip-centric behavior exhibited at concerts post-quarantine. Examples include taking repeated pictures of the film "like I was at a concert," a meme typically applied to taking photos of videos being streamed on laptops or phones. The meme's shift from these smaller screens to movie theaters reinforces the idea that post-quarantine, audiences equate moviegoing with streaming. The public experience they're striving for ignores the actual and reaches for the virtual. Fellow moviegoers don't matter, online followers do.

Elsewhere on social media, people are calling attention to the fact that they're taking photos in a theater. A popular post points to someone taking a photo of a naked J. Robert Oppenheimer (Cillian Murphy) in a public screening, only to realize their flash was on. The joke relies mostly on the humiliation that everyone knows you've documented a particular scene, and less on the transgression of using your phone in a theater. In the viewer's eye, the problem (and potential for viral humor) lies not in them taking a photo, but more in them getting caught. (Grainy images of naked Oppenheimer have since become memes in their own right.)

Both of these trends make the moviegoing experience more about the photographer than the content of the film. The real focus here is not the thing in front of the camera but the person smirking behind it. The same goes for people scrolling TikTok or otherwise using their phones during a film: In breaking the immersion of a theatrical experience, they're calling attention to their own actions instead of the movie, whether intended or not.

You may be watching a film about Barbie or Oppenheimer, but for these audience members, the only main character is themselves.