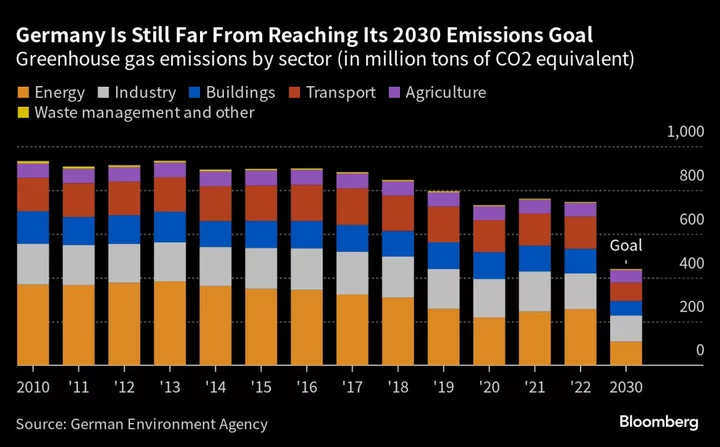

A financial official from an island that’s among the world’s most vulnerable to global warming has a plan to quickly increase the amount spent on climate solutions in developing nations. And his plan requires little additional spending by rich countries.

“If you focus only on grants, only on people transferring money to you, you’re never gonna get the scale we need to save the planet," says Avinash Persaud, a Barbados-born, UK-raised development economist who was previously a banker in the City of London. His target for spending on emissions-reducing projects alone by developing countries is about $1.5 trillion per year — or seven times the sum rich countries currently give in overseas development aid for all causes, including health and poverty reduction.

In a recent interview with Bloomberg Green, the impatient 56-year-old who serves as the financial adviser to Barbados Prime Minister Mia Mottley explained that the obstacle is better understood not as the lack of money but how to adjust the rules of global capitalism to end the prevailing climate-finance deadlock.

“The problem is that everyone believes someone else should be doing more. Why? Because it’s a cost to them to do it,” Persaud says. “So if we can reduce the cost for them, they won’t spend their time pointing their finger at someone else — they will get it done.”

His proposals — under the Bridgetown 2.0 agenda — face enormous challenges that could prevent implementation. But they’re being taken seriously. A summit in Paris this week will bring together the heads of government from more than 100 countries to grapple with financial scarcity as the single-biggest impediment to climate action. Bridgetown solutions — devised by Persaud’s team and championed by Mottley, who is co-hosting the event alongside French President Emmanuel Macron — will take the spotlight across two days of meetings about how to reform the World Bank, the International Monetary Fund and other multilateral lenders.

How did political players from a small-island nation end up at the center of a longshot push to rewire global finance for the climate era? It helps that Mottley’s star-turn speeches at United Nations podiums tend to get far more views on YouTube than the population of Barbados. Her speech at COP26, for example, has been watched more than every other speech by every world leader that year — combined.

But Mottley hasn't been relying on her speechmaking prowess or her moral stature as the face of an island with extraordinary vulnerability to rising seas and violent storms. She’s also been pulling political levers by fronting practical solutions that are designed to unlock trillions of dollars in private spending for dealing with climate change. That program has been assembled by Persaud, whom she first met while studying at the London School of Economics.

Under the original Bridgetown Initiative, named after the capital of Barbados, Persaud first pitched an ambitious set of solutions to the climate-finance deadlock last year. Those proposals, aimed chiefly at reforming the IMF and World Bank, failed to gain the backing needed for policy changes within giant institutions mostly controlled by a small group of wealthy nations. But his ideas — helped by Mottley’s speeches and diplomatic acumen — succeeded in capturing outsized attention.

Now Persaud is back with Bridgetown 2.0, a brief policy document that has been circulating in its current form among climate diplomats since April but hasn’t been previously reported in full. He hopes to bring to his cause some of the leaders gathering in Paris for this week’s meeting, known as the New Global Financing Pact. The summit is expected to draw the likes of German Chancellor Olaf Scholz, Chinese Prime Minister Li Qiang, Brazilian President Luiz Inacio Lula da Silva and the leaders of the IMF and World Bank. (Bloomberg Philanthropies is one of the summit’s official sponsors.)

Persaud’s ideas are specific and pragmatic, even if their political feasibility remains largely untested. The new Bridgetown plan is “comprehensive and very ambitious,” said Frank Schroeder, senior policy advisor on global finance and economics at E3G, an environmental think tank.

Bridgetown 2.0 aims to create currency exchange guarantees, add disaster clauses to debt deals and tweak the rules to enable much greater lending from multilateral lenders. Another proposal would enact a levy on emissions from the shipping industry or impose a fee on oil exports. Doing these things would be difficult, Persaud admits, but can unleash trillions of dollars in finance without simply relying on calls for increased aid from wealthy nations.

Those calls, no matter how righteous, have a way of going unfulfilled — particularly when the rationale is global warming. Developed nations first agreed to muster $100 billion per year in climate finance payments to developing countries back in 2009 and have yet to fulfill that goal. Unmet financial promises often lead to breakdowns in climate talks, such as the preliminary UN meeting last week in Germany that concluded last week without significant progress. Finance will also play a prominent role in the year-end COP28 climate summit that will be held in Dubai.

From Persaud’s point of view, fixes for climate finance need to be sorted in three financial buckets. Into the smallest bucket goes that $100 billion per year of promised grants that cover mounting damages to life and property wrought by climate change. Persaud witnessed first-hand why large grants are necessary when he examined the aftermath of Hurricane Maria in 2017 on the island state of Dominica, a neighbor to Barbados. A single storm led to losses valued at more than 200% of the country’s gross domestic product.

“These are for people who do not have any resources,” he says. “Insurance companies are not going to insure them. Countries can’t borrow for this, so we need grants.”

Listen to Avinash Persaud’s extended interview on the Zero podcast.

The smallest bucket is still a lot of money. All the overseas development aid from rich countries each year accounts for $200 billion, and it goes for every cause from health care to poverty reduction. Persaud acknowledges that there’s no way those countries are going to increase that aid by 50% just to address climate impacts.

Instead, he champions a proposal to tax shipping’s carbon emissions that could help toward the $100 billion fund. The International Maritime Organization will debate such a tax next week when it meets in London. Another funding option he’s suggested would be a small fee on oil exports, which could be modeled on an existing polluter-pays model that’s used for oil spills.

Persaud’s second bucket would need to be filled with about $300 billion. This is money that governments ought to be able to borrow, because the cost-savings from spending it on protective infrastructure should be manifestly clear. “All very unglamourous stuff but very important,” he says of such spending on climate defenses. “You don’t make money from having a seawall,” he offers by way of an example, “but you save money from all the times that the capital city is not flooded because you’ve got a new seawall.”

Lending to pay for seawalls, early-warning systems for extreme weather events, or action plans during heat waves can come from multilateral development banks. These institutions, however, are currently under some of the same constraints as private banks. They all need a certain amount of money in reserve to ensure they can repay the bonds that raise the capital they lend to countries.

Persaud and many other economists argue that lending institutions backed by sovereign governments are not like other private banks. The reality of their government backing should make it possible to lend a lot more money against the limited reserve they already have; Persaud thinks this increase in lending could be hundreds of billions of dollars more each year.

There’s currently a review happening that would allow the World Bank to retain its AAA credit rating while starting to lend more money. The odds of a dramatic change are long. “No one’s going to fully implement it,” said Karen Mathiasen, project director with the Center for Global Development and who previously served as acting US executive director at the World Bank. “But the review is underway.”

Persaud’s final Bridgetown 2.0 bucket, and by far the largest, already has about $1 trillion — and needs an additional $1.5 trillion, according to a group of UN-backed experts. Most of this is invested in clean-energy projects, such as building a solar farm, that generate real returns. It’s the type of money that should be attractive to private investors in rich countries because it’s actually profitable.

But for all the evidence that solar and wind are the cheapest sources of power, there’s still not enough capital flowing into these green transition projects in developing countries. Persaud took a deep dive into the costs of renewable energy projects in developing countries and compared them to those in developed countries. He concluded that supply-chain troubles and difficulties in execution presented smaller obstacles for investors than something that would seem relatively trivial: currency-exchange rates.

When foreign investors back green energy projects in developing countries, they’re doing two things. First, they’re using their dollars, pounds or euros to buy reals, pesos or rupees, and then they’re using that local currency to take a stake in a local project. When they want to cash out, they do the reverse. The project might be profitable, but if the value of the local currency depreciates, it eats away at the gains.

To guard against these currency risks, many emerging-markets investors, in projects green and otherwise, pay for currency hedges. Those instruments are also expensive. Persaud, who used to trade emerging-markets currencies in his finance career, says investors often overpay for hedges. The currency risk adds a layer of cost and complication, both of which deter otherwise willing investors.

That’s why Bridgetown 2.0 calls for the World Bank and IMF to offer a solution by backing a separate agency designed to reduce the cost of hedging for investors. The multilateral lenders can do so in the form of currency-exchange guarantees and thus trim off the “overpayment” that’s currently made in the open market. In turn, that would boost the return on clean-energy projects and make many more of them bankable.

Persaud’s estimation is that a facility with $100 billion to offer in such guarantees could unlock an additional $1.5 trillion in annual spending on clean energy in the developing world. But not everyone is convinced it will work. “Using scarce aid money on derisking or juicing up returns for the private sector has failed to generate the promised catalytic effect in all but a handful of instances,” said Sony Kapoor, professor of climate, geoeconomics and finance at the European University Institute.

But the world also cannot wait for perfect solutions. “If the global south is serious about changing the conditions under which we operate, removing the imperial shadow, looking for a fair deal with respect to access to finance,” Mottley said on the sidelines of the annual meeting of the African Export-Import Bank in Accra, Ghana on Tuesday, “then I believe that it is possible to shift together.”

The goal of this week’s Paris summit is to create a new accord between rich and poor countries, helping them deal with not just climate change but also rising inequality and loss of biodiversity. It’s happening at a time when, following the economic impacts of the pandemic, more than 50 countries are in distress because of extremely burdensome debt payments. But Persaud’s ideas are also getting attention now because the reform of the World Bank and IMF has become a strategic benefit to Europe and the US. It’s potentially a way to counter China’s growing economic influence. Beijing is now the biggest lender to many developing countries.

But that doesn’t mean the Paris meeting is likely to result in immediate changes. Instead, it could produce a list of clear targets and perhaps timelines that will be endorsed by the world leaders attending. “The momentum for change is growing,” said E3G’s Schroeder.

The annual meetings of the World Bank and the IMF in October in Morocco could be the first chance to secure the votes needed. What’s clear now is that changes to the global financial system are necessary, but they won’t work if the fixes are on the margins.

“The system is broken,” says Persaud. “If it’s not fixed, it will just be brushed away as irrelevant.”

--With assistance from Oscar Boyd, Ekow Dontoh and Eric Martin.