After generations of trying to produce the power of a star on Earth, a successful nuclear fusion ignition happened in the middle of a December night and was over in 20-billionths of a second.

That's more than 100 billion times shorter than the Wright Brothers' first, 12-second flight — but a brief, shining moment that could have even bigger implications for humanity.

But while the science teams at Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory are still buzzing over their Wright-Brothers moment, we only remember that name because their third flight stayed in the sky for 39 minutes.

The nuclear fusion reaction must be repeated, extended and scaled before the comparison sticks. And the race is on to make it work.

"But that's what makes it so exciting, right?" lead scientist Tammy Ma told CNN. "The potential is so great for clean, abundant, limitless, affordable energy. It will be tough. It won't be easy. But it's worth doing."

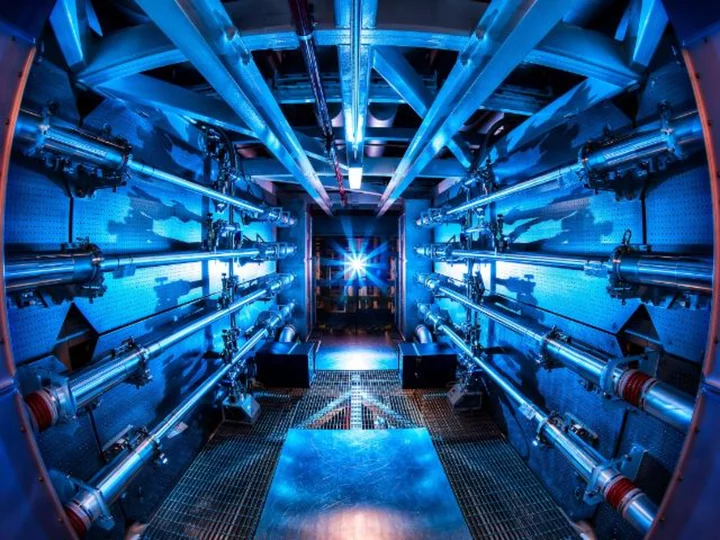

Ma's office is a giant box of lasers the size of three football fields in the corner of a 7,000-acre lab in Livermore. Running across the soaring white ceilings are miles of square tubes holding 192 of the most energetic lasers in the world, all snaking toward a round room at the center.

The very middle of this target chamber becomes the hottest place in the solar system every time they run a fusion experiment, and it is covered with enough gleaming machinery that J.J. Abrams used it to portray the warp core of the USS Enterprise in "Stark Trek Into Darkness."

With a legacy of delays and cost overruns, the National Ignition Facility was wryly nicknamed the "National Almost Ignition Facility," or "NAIF," by critics in Congress. If not for its work studying nuclear weaponry without the need for test explosions, the program might have lost funding years ago.

But now, for the first time since breaking ground in 1997, the National Ignition Facility can finally live up to its name. In December, 192 of the most energetic lasers in the world heated up a tiny pellet of hydrogen atoms with such force, they fused together to create helium and — most importantly — excess energy.

A little more than 2 megajoules of energy going into the target chamber became 3.15 megajoules coming out — a modest gain of around 50%, but enough to make history and allow scientists to call the experiment a true success.

The five attempts since have all failed to repeat it.

"We've learned a lot through those experiments," Lawrence Livermore Director Kimberly Budil said during a celebration of December's ignition. "And we're very confident we'll get back above that threshold. But it's still very much an R&D project at this point."

While some of the failed shots used less power than the successful one, others were unable to recreate the precision of the diamond capsules used to hold the hydrogen atoms.

"We made a number of modifications to try to compensate for the fact that the capsules weren't perfect and some of those worked better than others." Budil said. "And so the hope is always there. But if you look at the history of experiments that we've done, very small changes on the input bring very large changes in yield on the output side."

"Every time we do a shot, we are the hottest place in the solar system," Ma said as she pointed at the miles of mirrors which can amplify $14 worth of electricity into a force "a thousand times the power of the entire US electrical grid. But your lights don't flicker at home when we take a shot because we're taking a huge amount of energy and compressing it down into nanoseconds."

The facility was all built with 20-year-old technology and Ma said that if they were to rebuild it today — or build a legitimate nuclear-fusion power plant — "you would use new technology that is a lot more efficient, could shoot at much higher rates, with higher efficiency and very high precision."

So far, the nuclear-fusion field has been mainly divided into those that use lasers to spark ignition like a series of firecrackers, and those that deploy magnets strong enough to lift an aircraft carrier to control streams of plasma flowing around a doughnut-shaped machine called a tokamak.

In 2021, scientists working near Oxford used the magnet method to generate a record-breaking amount of sustained energy for five seconds.

"In ten years, they will be where we were ten years ago," Bruno Van Wonterghem, NIF's operations manager, said — a sign of how competitive the growing fusion race is becoming.

Even before December's successful shot, private investment in fusion technology tripled in 2021, with dozens of startups trying to tackle fusion's infinite challenges in novel ways. One Vancouver startup is attempting to harness a whirlpool of liquid metal to control neutrons, while alumni of the Lawrence Livermore Lab have spun off an idea for small, modular fusion reactors and count Bill Gates and Shell Oil as investors.

Helion Energy is making the boldest promises of the startup lot, and attracting some of the biggest backers in tech, including a $375-million investment from Sam Altman, the CEO of Open AI. Helion claims its prototype the shape of huge dumbbell will fire plasma rings at a million miles an hour and demonstrate the ability to produce electricity through fusion by next year.

After Microsoft announced on Wednesday a commitment to buy 50 megawatts of electricity from it in 2028, Helion says it will build their first plant in Washington state. But this the first-of-its-kind fusion power purchase agreement is a modest one, accounting for just around 0.04% of the clean power Microsoft bought in 2022.

The International Atomic Energy Agency doesn't expect electricity from fusion to be produced until the second half of the century, and as difficult as it is to control sun-hot plasma, it's been equally hard to control the cost of making it.

"At the moment, we're spending a huge amount of time and money for every experiment we do," Jeremy Chittenden, co-director of the Centre for Inertial Fusion Studies at Imperial College in London, told CNN. "We need to bring the cost down by a huge factor."

Now that they have their Wright Brothers moment, Ma is convinced the world will eventually fly, work and live on fusion.

"If we, as the US, decide we're going to do it, we can do it. It's only a matter of time. It's a matter of money," Ma said. "It's a choice we have to make together. And I do believe we will see it in the next few decades.

"For sure."