The battery-powered BMW iX is a technological marvel. It travels up to 321 miles on a charge, its glass sunroof goes opaque at the touch of a button and you can turn up the stereo by twirling a finger near the dashboard. At the moment, one of these magical machines is on offer in Los Angeles for $80,195, a 17% discount on the sticker price.

If that’s a bit rich, there’s an Ariya, Nissan’s all-new EV, listed for $36,690 in Kansas City — a discount of 18%. More affordable still is the $29,990 Hyundai Kona Electric available in Atlanta. That’s a 31% discount, making it almost as cheap as the gas-burning version.

To borrow a tired advertising mantra, there’s never been a better time to buy an electric vehicle, at least in the US. The American market now has more than 50 unique models to choose from, over double the options two years ago. As production volumes for battery-powered cars catch up with demand, there’s also a glut of supply. EV inventories in the US are up fivefold over the past 12 months, according to digital listing platform CarGurus.

“For consumers now, it’s great,” says Kevin Roberts, director of industry insights at CarGurus. “EVs are becoming much more affordable than they were a year ago … and we’ve covered a lot of that early-adopter demand.”

Would-be buyers should act fast, though (to borrow another advertising mantra). The excess inventory won’t last long.

Amid rising interest rates and steady inflation, pricing has been a major hurdle for EV adoption in the US. In June, almost two-thirds of US car shoppers surveyed by JD Power said they were “overall likely” to buy an electric car, but many couldn’t find one in their price range. As recently as October, the average listing price for an EV on CarGurus was 28% higher than that of a gas-burning vehicle.

Adoption is also affected by allocation formulas, which determine where new cars are shipped. EVs coming out of US factories are still disproportionately directed to dealerships in states like California that have regulations restricting gas-car sales by certain dates.

“You’re going to find large swaths of the country where you might not find a dealership with one EV on the lot, let alone a number of them,” says Roberts at CarGurus.

But the EV premium is already starting to slip, a trend Tesla Inc. set off by steadily slashing prices on its two most popular models this year. Ford followed suit, wacking up to $10,000 off the sticker price of the F-150 Lightning pickup truck. On CarGurus, average prices are down over the past 12 months for Toyota’s bZ4X (-10.3%), the Kia Niro EV (-8.6%) and the Chevrolet Bolt EUV (-6.4%), among others.

Mahi Manchala, an IT director who commutes from New Jersey to Manhattan, just swapped her gas-powered Infiniti for a top-of-the-line Mercedes EQS priced at $130,000, 6% off the window sticker. The dealer even paid for a home charger, which cost almost $2,000 with installation.

“It’s the ultimate in luxury,” Manchala says. “And for what I got, it was the best deal.”

This intoxicating moment for consumers is simultaneously a bit of a hangover for carmakers, who have been grumbling about a slowdown in EV demand and stressing the Tesla-led price wars. “With price discounts of some of the other guys [at] more than 30% … I would say this is a pretty brutal space,” Mercedes Chief Financial Officer Harald Wilhelm said on a recent earnings call.

Indeed, the EV glut is spooking many auto executives into pumping the brakes on production. Ford has delayed or put on hold $12 billion in EV spending, while slowing production of the Mustang Mach-E, its most popular electric model. GM delayed some models and abandoned a goal of building 400,000 EVs by mid-2024.

But even with those growing pains, it’s hard to overstate the momentum of the electric vehicle market. US EV sales are are up almost 2.5 times over the past 12 months. In the third quarter, EVs as a share of new car sales topped 10% in 11 US states, according to Atlas Public Policy, and they hit 7% in Texas — the country’s second largest car market after California.

“The stories being written that it’s falling apart are just dead wrong,” says Elaine Buckberg, formerly an economist at General Motors and currently a senior fellow at Harvard University.

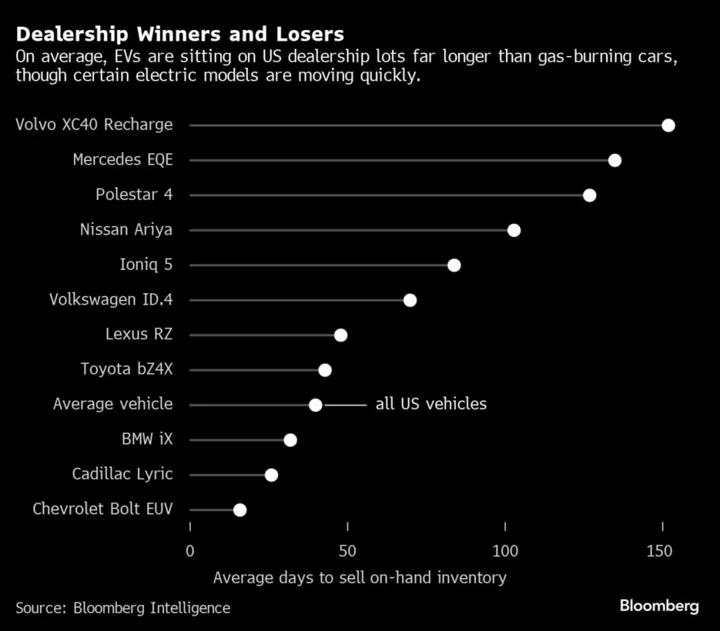

Part of the nuance is that the spread between EV supply and demand isn’t uniform — it fluctuates depending on the model. Vehicles hitting a sweet spot between price, range, features and design are selling quickly. The Bolt, for example, which has a relatively high range and a relatively low price, is still in short supply. Ditto the Cadillac Lyric, a swanky SUV that’s meant to compete with German luxury brands but starts under $60,000.

“I wouldn’t assume buyers have lost interest in electric vehicles,” says Ingrid Malmgren, policy director at nonprofit Plug In America. “I don’t think that would accurately represent the situation.”

At AutoNation Inc., which runs about 250 dealerships in the US, EVs have lately been sitting on the lot for 60 days on average, twice as long as gas vehicles. But the weak demand manifests “in pockets,” says Derek Fiebig, vice president of investor relations.

“The higher priced vehicles, it’s a little more difficult for them,” Fiebig said at a conference on Oct. 31. “The lower priced vehicles have qualified for the federal funds, which helps, and so those are moving pretty quickly.” (Some American-made trucks and SUVs under $80,000, and some cars under $55,000, are eligible for a $7,500 Inflation Reduction Act rebate.)

In other words, the growing EV market is developing leaders and laggards. “We’re going to start to see customers get a little more picky and I think pricing is going to be really important,” says Roberts. “It’s starting to look like the regular car market.”