It’s a perennial annoyance during quiet weekends in US suburbia: The roar of the neighbor’s lawn mower, the whine of a trimmer, the howl of the leaf blower.

If California has its way, the racket will soon be on its way out. The state, which has long been a leader in environmental policy, will become the first to ban the sale of new gasoline-powered lawn mowers and other landscaping tools starting next year.

The rule isn’t just a noise-control measure — it’s primarily aimed at reducing emissions from small off-road engines that are more polluting than all the cars in the state combined. The ban also sets up a new test of Americans’ willingness to embrace cleaner technologies in their daily lives, as they face growing restrictions on everything from gas appliances to conventional cars, and companies go all-in on electric.

The issue has sparked a debate that echoes the controversy over limits on gas stoves, which have faced opposition from some Republicans, gas companies and others who say the restrictions reduce consumer choice.

“For gas stoves and gasoline lawn equipment, we’re increasingly becoming aware of their impact on public health,” said Tony Dutzik, a senior policy analyst at environmental think tank Frontier Group. “If you’re a policymaker elsewhere in the country, you’re absolutely going to be looking at seeing how effective California is.”

Indeed, the California ban could start transforming the US suburban landscape, where lawns have long been a symbol of status and pride. Reach back far enough into time, and it’s fair to say gas-powered lawn equipment helped shape the post-war American dream, as returning veterans bought homes with grassy yards that required trimming.

“People didn’t choose to have a lawn in the ‘50s, they chose to have a house. And when you bought a house back then you had to have a lawn,” said Paul Robbins, dean of the Nelson Institute for Environmental Studies at University of Wisconsin-Madison and the author of Lawn People.

But the dream came at a cost. According to the California Air Resources Board, a state agency that regulates air quality, a typical gas-powered lawn mower emits as much pollution in one hour as driving a car 300 miles, more than the distance from Los Angeles to Las Vegas.

Gas-powered leaf blowers are even worse, producing not just pollution but also noise levels that can damage hearing and disturb wildlife. The tools require regular maintenance and fueling, which can be expensive and inconvenient. Electric technology is often quieter and cleaner.

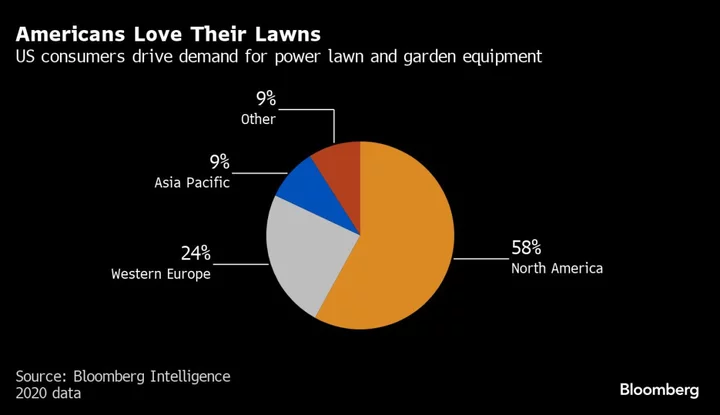

Since the post-war boom, Americans’ need to keep up appearances has become big business. In 2020, North America comprised 58% of the $25 billion global power lawn- and garden-equipment market, according to Bloomberg Intelligence. With almost two-thirds of US demand driven by households, manufacturers are deeply invested in getting consumers to go battery-powered as regulations tighten.

Read More: California Approves Ban on Gas-Powered Car Sales by 2035

Many homeowners and businesses have already made the switch, either voluntarily or in response to local regulations. Dozens of cities and towns across the country, from Naples, Florida to Washington, DC, have banned or restricted the use of gas-powered leaf blowers and other tools, citing noise and air quality concerns.

Hyattsville, Maryland, is among the local governments that offer incentives for trading in old gas-powered tools, while major retailers like Home Depot Inc. and Lowe’s Cos. are reporting higher sales of electric equipment in some markets.

Lawn equipment manufacturers say the bans reflect a reality they’ve long acknowledged: battery power is the future.

Stanley Black & Decker Inc. isn’t eliminating gas-powered lawn equipment from its line-up, but its priority is electrified devices. “What we’re putting our R&D efforts toward, what we’re putting our advertising toward, it’s all toward electrification,” said Christine Potter, president at the company’s outdoor unit.

Husqvarna, a Swedish manufacturer, hopes electrification will raise awareness of its robotic mowers, which work like Roombas for lawns — though they aren’t cheap, ranging from $700 to $32,000. It has competition from Honda, which has unveiled a new prototype of a battery-powered autonomous mower for landscapers, which learns routes from a human operator to repeat later.

Not everyone is on board with the revolution, especially due to cost. Potter says a hand-held electric grass cutter can cost up to 25% more than a gas-powered one, and a push mower as much as 50% more. And some users prefer the performance and durability of gas-powered tools, especially for large or tough jobs. Others worry about the battery life and charging constraints of electric models, along with the upfront expense.

“We completely support a responsible transition, but we oppose arbitrary timelines to ban the equipment,” said Andrew Bray, of the National Association of Landscape Professionals.

The California rule only applies to sales starting in 2024 — it doesn’t prohibit the use of existing gas-powered lawn tools and shops are allowed to sell out their inventory. It also provides $30 million in funding for rebates and other programs to help landscapers replace their equipment with zero-emissions versions.

Marc Berman, a Democratic lawmaker representing parts of Silicon Valley who wrote the law, hopes the measure will lead to more aggressive policies to eliminate gas-powered appliances, such as water heaters and pumps.

“The results are going to be a dramatic reduction in smog-forming pollutants and greenhouse gas emissions,” Berman said. “Some of the electrification of the home that we’re trying to encourage people to take advantage of, I think a lot of these same lessons could apply.”

--With assistance from Nadia Lopez.