Marco Weibel lived through one of his darkest days in June 2021. It was then that Swiss voters narrowly rejected enshrining the nation’s commitment to the Paris Agreement into law, leaving the country with no legally binding climate target.

Weibel, who works in waste management for the national train network, hadn’t campaigned in support of the referendum two years ago, assuming it would pass. But with a national vote on Sunday of a similar magnitude, this time over the country’s target to reach net zero emissions by 2050, he decided to get involved. As rush hour commuters poured into Zurich’s main train station last week, Weibel flitted among them handing out door hangers supporting the so-called Climate Protection Act.

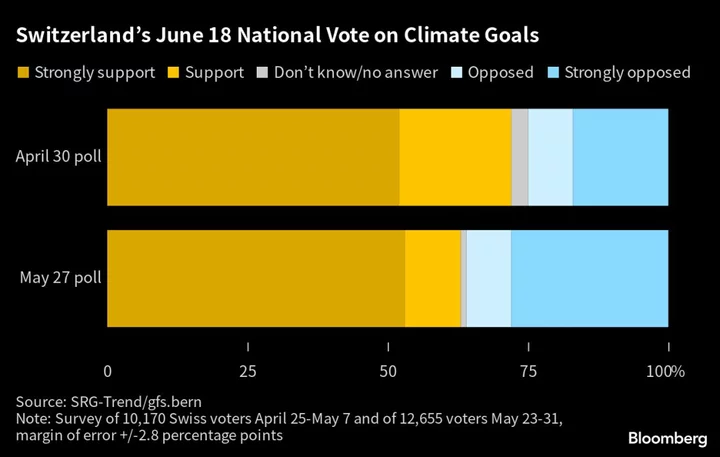

“We cannot lose this vote,” he said. The most recent polling shows the measure is likely to pass, although margins have been tightening.

Many national legislatures have passed climate laws, and all 10 of the world’s biggest economies have now committed to net zero targets. Switzerland’s distinctive approach to democracy means its voters will have an unusually direct say in how the government deals with reducing its emissions. Campaigns for and against the law will be familiar to anyone who watched the tug-of-war over the Inflation Reduction Act in US and most any other climate legislation introduced elsewhere: One side argues that urgent action is needed to slow global warming, the other highlighting what it claims are the painful changes that will have to be undertaken to get there.

In Switzerland, the campaign in favor of a net zero target is drawn from a broad coalition of 200 groups that includes political parties, scientists and activists who are presenting the measure as a chance to get the nation on track to meet its Paris Agreement target and ensure a smooth transition to a clean energy economy.

“For the moment, we have different laws treating climate topics in specific ways,” said Sophie Fürst, the co-campaign manager for the vote-yes group. “This law is really a frame for it. It refers to the Paris Agreement. It’s really important for Switzerland to fulfill its commitments.” Those commitments include cutting greenhouse gas emissions at 50% below 1990s levels by the end of this decade and reaching net zero by 2050.

After voters shot down the 2021 law, the Swiss government has been left with precious few legal mechanisms to ensure those goals are met. That’s in part why the Climate Action Tracker, a resource put together by a consortium of climate groups to keep tabs on countries’ green commitments, rates Switzerland’s target as “almost sufficient” while rating its policies as “insufficient.”

The upcoming vote is a chance to get policy and aspiration better aligned. It’s also a chance to preserve Switzerland’s natural resources and alpine environments that are under assault by rising temperatures. That includes the nation’s famed glaciers, which are melting at a quickening pace. Half of all glaciers across the Alps could disappear by 2050.

The reason Swiss voters will have a say on net zero emissions becoming the law of the land is because of the Swiss People’s Party (known by its German acronym SVP), a right-wing nationalist group that is the largest in parliament. When the legislature passed a law last year staking out a net zero target, the SVP was the only party in opposition. In response, it gathered enough signatures to get it on the ballot for a direct vote on June 18.

Switzerland’s People Power

The Swiss system of ballot initiatives — in force for more than a century — allows voters to have a direct say. Any recently passed law can be challenged via a referendum by collecting 50,000 signatures from citizens. The system allows for national votes, held four times a year, that are legally binding.

June 18 also features two other Swiss-wide measures — on the OECD minimum tax and on Covid rules — which are both expected to pass.

To turn voters off to net zero, the SVP and its allies have labeled it the Energy Eater Law. The campaign has sent out mailers — designed to look like a newspaper — to every household in the country. The campaign also raises the specter of gas bans, rising meat prices and the Alps being covered in solar panels. The vote-no campaign has also claimed the law will cause energy prices to soar, based on research done at the Swiss Federal Institute of Technology Lausanne.

The university, however, has taken issue with how the study is being cited. In an understated press release, it said that a “political party has chosen the most expensive — and least realistic — path for its electoral campaign, in which Switzerland would produce all its energy itself (notably by producing synthetic fuels).”

Judit Hecke, a climate policy analyst at the NewClimate Institute, a German nonprofit, was more blunt in her own assessment: “Everything it says in here is not true. This is not a healthy debate. This is literally fake news.”

Hecke is also responsible for updating Switzerland’s Climate Action Tracker entry. She noted that while the 2021 law overturned by voters included unpopular changes to taxes, the new version is focused on subsidies. That includes 2 billion Swiss francs ($2.2 billion) over the next 10 years to help replace fossil fuel and inefficient heating systems in homes and investing in innovation like carbon removal technology. Switzerland is home to Climeworks, one of the global leaders in the so-far undeveloped carbon-removal industry.

A white paper from ETH Zurich found that decarbonizing the Swiss economy could save households money — or cost them up to 600 francs in the most pessimistic scenario. Crucially, the research doesn’t factor in the benefits of decarbonization like cleaner air and more biodiversity, noting those “potential savings could by far outweigh the costs of decarbonizing energy provision.”

The investments are far from enough to get Switzerland, a country of 8.7 million, on track to meet its climate goals. But it offers a framework and defined targets that the government can outlay money for going forward.

“A lot of other countries, including much less developed countries, like Colombia, Chile or Vietnam, have already ratified net zero targets in their law,” Hecke said, adding that it was important for a wealthy country like Switzerland to show it was serious by doing the same.

Ultimately, of course, the voters will decide if it’s important. That reveals one of the key challenges of putting a climate vote directly to the people: The process is inherently about taking time to build consensus, and that’s an increasingly finite resource in the race to combat rising temperatures.

“Our main task is to mobilize people who are for the climate law to go and vote,” Fürst said. “We’re like, ‘We can’t lose, we don’t have any other options.’”

--With assistance from Claudia Maedler and Zoe Schneeweiss.