Businesses and the climate both stand to benefit from accelerated work to stem methane emissions within the oil and gas sector, JPMorgan Chase & Co. said in a report that amounts to a call for more action — and investment — targeting leaks of the potent greenhouse gas.

The white paper released Wednesday outlines the economic and environmental opportunity for methane abatement, while also encouraging oil and gas companies to set emission intensity targets, end routine flaring at oil wells and consider third-party audits that could drive additional improvements.

It’s the first move of its kind among the biggest US banks — one that could set the stage for more capital to flow to methane-stifling work and potentially help encourage oil industry lenders to impose conditions requiring it, said Andrew Baxter, senior director for business and energy transition at the Environmental Defense Fund.

The Wall Street giant’s report potentially “lays down the gauntlet for their peers to start moving on methane emissions,” Baxter said. “The messenger always matters — and if your biggest lender is JPMorgan and they’re drawing a line in the sand about what they believe is best in class regarding methane emission management,” that could “attract the attention of their clients as well.”

The paper is an outgrowth of JPMorgan Chief Executive Officer Jamie Dimon’s 2021 annual letter urging “tangible, cost-effective solutions to reduce emissions,” including minimizing methane leaks and “virtually eliminating wasteful flaring of natural gas.”

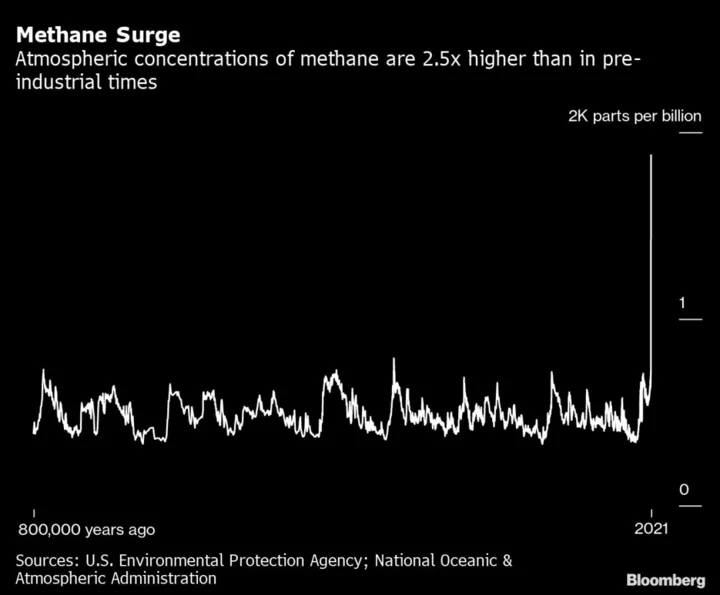

The issue has taken on new urgency — and will be in focus during UN climate talks in Dubai later this month — because methane is such a powerful greenhouse gas that has more than 80 times the warming power of carbon dioxide during its first two decades in the atmosphere. Curbing releases from the oil and gas sector — where it’s vented intentionally from wells, burned off as a waste product or simply leaks from equipment — is also one of the lowest-cost and least technologically challenging ways to keep the gas out of the atmosphere.

The JPMorgan report comes amid a series of state-backed efforts targeting methane cuts. European Union negotiators said in a statement Wednesday they struck a deal to curb methane releases from fossil-fuel infrastructure and plotted a course to monitor and limit the emissions associated with imported energy sources. China said earlier this month it will boost monitoring, reporting and data transparency to reduce releases of the super-potent greenhouse gas.

Reductions represent a prime opportunity for companies seeking to curtail greenhouse gas emissions from their operations. Methane released from venting, flaring and leaks represents around 55% of the operational emissions from the oil and gas sector.

Even so, investments to address methane have been held back by “a lack of reliable, real-world data” JPMorgan says, noting a surge in emissions-monitoring and measurement technology, from handheld devices and plane-based sensors, that promise to shrink that barrier.

Methane releases are severely underreported; a recent study using satellite data estimated emissions from the oil and gas sector are 30% higher than reported to the UN. Even so, it’s not clear that better data will drive more aggressive action.

“As companies measure and report more real-world emissions the numbers may go up, and we need to recognize that as a sign of progress,” said Ben Ratner, report co-author and executive director of corporate sustainability at JPMorgan Chase. “The market should understand that a company that reports high methane numbers based on good data is farther along in continuous improvement than a company that reports low methane numbers based on desktop estimates.”

Economics have also held back action — even though much of it could be implemented at no cost or pay for itself over time, as methane can be captured and sold. However, it can take time to see profits from this abatement work, compared to other opportunities within a company’s portfolio, meaning methane investments may be sidelined in favor of initiatives with swifter returns.

Those economics are likely to improve as companies evaluate potential future carbon prices, said the report co-author, Gissell Lopez, who is executive director of the Center for Carbon Transition at J.P. Morgan.

“Projects that five years ago were not economically feasible, now, with the incorporation of carbon pricing,” may offer a return on investment, Lopez said.

Author: Jennifer A. Dlouhy