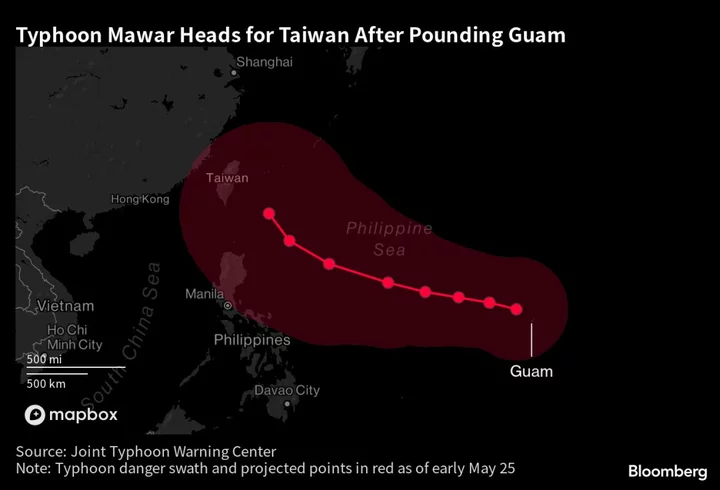

As Typhoon Mawar neared the coast of Guam early Wednesday, it also drew attention to an uncomfortable fact of US military strategy: Many of America’s most strategic assets are in places increasingly threatened by extreme weather events, rising seas and other consequences of climate change.

The Navy moved ships out to sea before the storm hit, standard procedure when bases prepare for hurricanes. The storm generated winds of 140 miles per hour (225 kilometers per hour) — the National Weather Service’s offices were “vibrating,” an official said — and waves of at least 46 feet (14 meters). The storm surge is expected to cause significant flooding, worsening the dangers for residents and putting new demands on the military.

It isn’t the first time and it’s unlikely to be the last. In 2019, a Department of Defense report on climate impacts noted that repeated flooding at Naval Base Guam was already limiting operations and activities for the Navy Expeditionary Forces Command Pacific, the island’s Andersen Air Force Base, submarine squadrons, telecommunications, “and a number of other specific tasks supporting mission execution.”

Considered one of the most critical US military installations in the western Pacific, Guam has for 125 years extended US sovereignty 8,000 miles from Washington. The island is about 2,100 miles from the North Korean capital of Pyongyang. It is closer still to Taiwan, which President Joe Biden has committed to defend if attacked.

“By virtue of having an American territory in Guam,” said Bruce Jones, director of the Project on International Order and Strategy at the Brookings Institution, “it gives the United States the ability to operate on home soil, two-thirds across the reaches of the Pacific.”

In short, Guam has for decades helped protect the international order and remains “an essential operating base for US efforts to maintain a free and open Indo-Pacific region,” the Pentagon wrote in its 2022 quadrennial National Defense Strategy. In January, the Marine Corps opened its first new base in 70 years on the island, part of an agreement to reduce the US military presence in Okinawa, Japan.

It’s hard to mobilize a military response if, for example, “your most important rear logistics base is under three feet of water,” Jones said. “These kind of events, if they’re not adequately defended against and quickly recovered from, really, really throw a spanner in the works in terms of our ability to respond to crisis scenarios in Asia.”

Those recoveries are expensive. Bases along the US Gulf and East Coasts have seen mammoth storms cause massive damage, including North Carolina’s Camp Lejeune, which suffered $3.6 billion in damage by Hurricane Florence in September 2018 and Florida’s Tyndall Air Force Base, which category 5 Hurricane Michael wrecked a month later and may cost $5 billion to rebuild.

“The challenge with planning on climate risk is you can’t use the past as well to predict the future,” said Sherri Goodman, a senior fellow at both the Wilson Center and the Center for Climate and Security, who in 2007 coined the now common description of climate change as a military “threat multiplier.” Storms are going to get stronger, with higher winds and more rain and flooding, she said, but that’s not necessarily precise enough to inform military budgets in a practical way.

The Pentagon is encouraging its military planners to think more seriously about these risks. Last year the department’s Wargame Incentive Fund budgeted $3 million to fund five war games focused on climate-related crises in South and Central Asia, designed to help the Indo-Pacific Command, which includes Guam, identify and adjust potential weaknesses. Last month, the military opened its DOD Climate Assessment Tool, called DCAT, with allies in Europe and Asia. The program combines climate models, historical data and flood models to simulate potential changes at 2,300 DOD sites globally.

The Navy, like the other Armed Forces, has in recent years issued global planning guidance on how to build, train and fight under changing conditions. Those efforts are accelerating, with climate impacts. Days after taking office, Biden signed an executive order that built climate change formally into national-security strategy.

“They knew this kind of stuff was coming,” Jones said. “They’ve been working at hardening their facilities to deal with exactly these kinds of scenarios. And in the aftermath we’ll see whether they did or not.”

--With assistance from Kevin Varley.

(Corrects to say Guam is located in the western Pacific.)