Germany’s Greens attacked their highest-ranking cabinet ministers at a party convention near Frankfurt this weekend. Nominally, the subject was European Union asylum rules, but that was largely a proxy for growing dissatisfaction over the party’s role in running Europe’s largest economy.

Buffeted by scandals, policy setbacks and fading support, the pressures of government are getting to Germany’s Green party, which has drifted into crisis along with the rest of Chancellor Olaf Scholz’s three-way coalition.

The decision by Vice Chancellor Robert Habeck and Foreign Minister Annalena Baerbock to wave through tighter restrictions for refugees “hurts me, it disappoints me,” Aminata Toure, integration minister in the state of Schleswig-Holstein, said at a rowdy gathering of about 100 delegates in the spa town of Bad Vilbel.

“It also tore me up” to abandon personal beliefs for the sake of a political compromise, Baerbock said at the party convention, pleading for understanding and support.

When the Greens joined Scholz’s alliance at the end of 2021, they were seen as the motor of Germany’s climate revolution. But a year and a half later, the party’s on a downward slide and is struggling to find a way to turn the corner.

The troubles for the once high-flying Greens reflect deeper issues running through Scholz’s combative coalition and raise questions about his government’s ability to confront the many challenges facing Germany. With the breakdown of the Greens as the driving force of innovation, Scholz’s whole government runs the risk of deadlock, creating a power vacuum at the heart of Europe.

Read More: Europe’s Economic Engine Is Breaking Down

On a talk show on public broadcaster ARD late Sunday, Habeck was confronted with a poll that showed only 20% of Germans are happy with the government. The economy and climate minister didn’t push back.

“I’m also not happy with the federal government,” he said. Although the Scholz’s administration managed to deal with the gas crisis and rein in energy and food prices, “we have not delivered a shining performance,” he added. “So we can’t be content.”

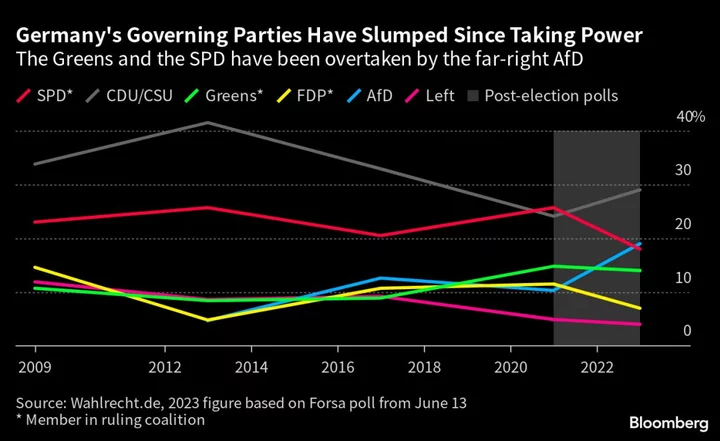

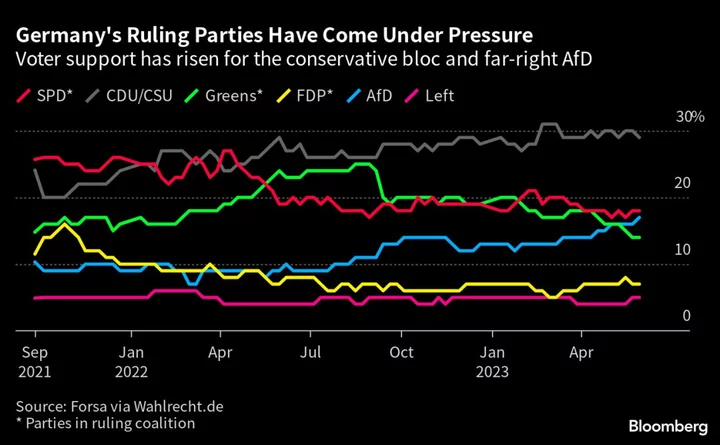

Amid incessant infighting, all three parties have fallen behind the conservative Christian Democrat-led bloc and the far-right Alternative for Germany in the polls. Support for the Greens has also now slipped below their 2021 results, joining Scholz’s Social Democrats and the business-friendly Free Democrats.

The Greens, which have clashed frequently with the FDP in recent months, have responded to their fading momentum by pushing too far, too fast. That’s played into criticism that they’re an ideology-driven elite out of touch with the real world.

“This is a party that could have made it into the chancellery,” said Sudha David-Wilp, a senior fellow at the German Marshall Fund. “But now the Greens are in a situation where ideology gets in the way of being a governing party. And they feel pressure to accelerate and reach certain goals without being pragmatic.”

Habeck has particularly been in the line of fire. The 53-year-old, who was once seen as a contender for chancellor, has gone from one of the country’s most popular politicians to fall below Scholz and ranked on par with Finance Minister Christian Lindner from the Free Democrats, according to a recent Forsa poll.

His change in fortunes stems from a series of blunders, and a campaign by the influential Bild tabloid that labeled the party’s initiative to end Germany’s reliance on traditional gas- and oil-powered furnaces as “Habeck’s heating hammer.”

The bitter debate over the reform is indicative of the party’s struggles to communicate its policies in a way that doesn’t stoke anxiety, which is already high amid Russia’s war in Ukraine and Germany’s economic struggles.

Read More: Europe’s Green Transition Under Attack as Political Costs Rise

Rather than right-wing opposition, the Green party’s chief nemesis is the FDP. The pro-business liberals have suffered a series of defeats in state elections and have taken a more aggressive stance within the government to lift its fortunes. Climate policy is a key point of contention. Recent tussles include holding up a European Union ban on combustion-engine cars.

Prodded by the FDP, Scholz’s administration also weakened emissions goals for Germany’s dirtiest industries. Starting next year, the coalition government wants to track progress on emissions by focusing on economy-wide figures instead of the current sector-by-sector goals. The new approach will allow less-polluting industries to compensate for dirtier ones.

Now, Lindner is gearing up for a fight over budgets in the name of defending taxpayer money and upholding the country’s tradition of tight spending. Scholz has been notably absent in the feuds, letting the Greens and the FDP trade barbs in public and allowing frustration with the government to grow.

Read More: German Slump Emboldens Finance Chief’s Drive for Budget Cuts

Internal divisions have also surfaced. After EU interior ministers agreed on tighter asylum rules, the Greens’ leadership duo of Omid Nouripour and Ricarda Lang were at odds. While Nouripour defended the plan, Lang sided with the party base and criticized it, saying the EU proposal wouldn’t do justice to “the suffering at the external border.”

At the convention, party members called on Habeck and Baerbock to change the asylum agreement. A majority voted for a proposal that called on the German government and the EU parliament to soften regulations for women and children. It was a compromise between more radical demands for a complete rejection and a pro-government position.

In the heating dispute, an initial proposal was leaked — according to Habeck by the FDP — and cast in a way to suggest homeowners would be forced to rip out their furnaces in a few years at enormous expense. While the focus was on new installations, ambiguities in the legislation stoked these concerns. In the process, the Greens lost control of the narrative and never got it back.

Habeck had fired back, saying his critics were spreading “insults” and “lies” not just to derail the heating bill, but to discredit the overall implementation of climate protections. But the Greens have struggled with that as well.

An unused heat pump at the party’s headquarters in Berlin is emblematic of its struggles to match vision with reality. In 2019, when Habeck and Baerbock were leading the Greens, they wanted to show how Germany can shift to cleaner energy, but the project in the pre-war building in central Berlin got bogged down in technical and bureaucratic issues.

Habeck’s reputation was also damaged by allegations of nepotism, which contributed to a setback in a regional election in the city-state of Bremen last month. A close ally resigned last month after an investigation into his involvement in appointing a friend to run a key government agency.

To rescue one of his key reforms, Habeck had to accept a watered-down deal with Scholz’s Social Democrats and the FDP. It foresees an exemption for homeowners on the fossil-fuel heating ban if their community hasn’t presented plans for expanding district heating. Big cities have been asked to present such proposals by 2026 and smaller towns by 2028. The fudge makes it even harder to reach climate goals in the building sector.

After leading efforts to wean Germany off Russian energy, Habeck saw the heating bill as the next stage toward greater energy security, which means less reliance on imported fossil fuels in favor of power generated from local renewable sources. But he admitted he misread the situation and didn’t expect the heating bill to become so contentious.

“Maybe we — meaning the people in Germany — were just exhausted, crisis-weary,” Habeck said at a conference after the heating deal was reached. “Something happened here, I didn’t sense it.”

--With assistance from Petra Sorge and Iain Rogers.