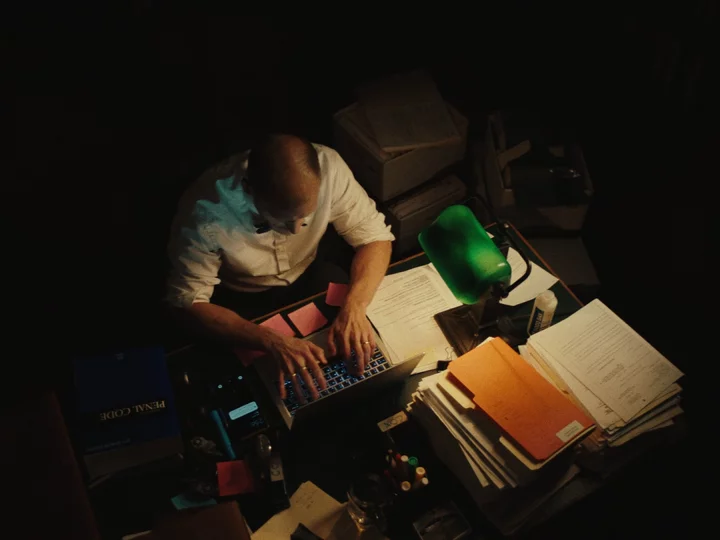

In a pre-climactic scene from new short documentary film Forgiving Johnny, a Los Angeles Public Defender named Noah Cox is talking about paper. Reams upon reams of paper that, viewers learn, are essential to whether or not indigent clients will get a fair shot in front of the judge.

"Paper equals time," Cox says to the camera in a dimly lit office, previously shown with boxes and stacks of sheets of paper. "Cases are limited by time. Some cases take thousands of pages." Thus, one is to conclude after learning of the millions of case files stored away in dusty warehouses, there is simply not enough time to shuffle all this paper across a single attorney's desk, let alone into pathways to rehabilitation.

In many ways, Forgiving Johnny uses paper as a stand-in for injustice, a bureaucratic flaw in the criminal justice system entangling 160 million case records that, until recently, made it all but impossible to appropriately serve many of Cox's clients, especially the 10,000 people with developmental disabilities sent to prison every month in the U.S., the film relays.

SEE ALSO: ‘Dreaming Whilst Black’ review: A sharp critique of systemic obstacles still blocking Black filmmakersForgiving Johnny zooms in on the 25 percent of incarcerated people that report having a developmental disability. It's a disproportionate reality that the film conveys through a single case study of a client of the Los Angeles County Public Defender’s Neurocognitive Disorders Team — someone Cox says was "predestined" to have a life of difficulty, with the potential for any contact with an inadequate justice system to be excessively punitive. Broadly, people with disabilities are overrepresented at all stages of the criminal justice system, according to the Prison Policy Initiative, with 40 percent of people in state prisons reporting a disability.

Johnny Reyes, Cox's aforementioned client and the film's main subject, was on his way toward joining that statistic. Instead, he became one of the first California residents to be diverted from a prison sentence into appropriate treatment under a new state law, and his experience served as a case study for the department's latest technological innovation.

Johnny and the search for the ark

A Breakwater Studios film, Forgiving Johnny was executively produced by NBA All-Star Karl-Anthony Towns and directed by Academy Award-winning Canadian filmmaker Ben Proudfoot, his latest installment in an ongoing social impact documentary series known as Impact Films, led and funded in part by digital business services company Publicis Sapient. The firm is behind a massive digitization effort at the Los Angeles County Public Defender's Office that debuted in 2020, and it uses the Impact Films series to showcase this and other clients' most transformative services. In 2022, Proudfoot directed Impact Film's first entry, Never Done, which tells the story of a woman seeking rental assistance amid the COVID-19 pandemic.

The artistic throughline of the film — as the title suggests — is the complicated path to forgiveness when one has done wrong. But Reyes' personal story and Cox's compelling articulation of the role of public defender — leadened only by a brief pause to discuss the attorney's history as a school bully — propose that restorative justice models are on the brink of being widely accessible, rather than rarities.

In addition to being a cry against the dominant leap towards conviction for these types of cases, the short film is also a treatise on the suffocating limits of outdated bureaucracy, seen in flashes of overfilled warehouses and desks piled with anxiety-inducing disorder. It introduces the county's new digital resources — including a data entry and case management system that also makes use of machine learning — as life-changing.

Reyes in 'Forgiving Johnny'. Credit: Breakwater Studios / Publicis SapientJames Kessler, senior vice president at Publicis Sapient, explained to Mashable that without the new system, the role of public defender is a lot like that of fictional artifact hunter Indiana Jones.

"You know the scene at the end of the original Raiders of the Lost Ark movie, where they're burying the ark in the giant government warehouse? Well, those things actually exist, and they exist in Los Angeles County. For attorneys like Noah to do their job, they have to go to warehouses like that to get that information, and that's incredibly inefficient. Now he can do that from his laptop, sitting at his dining room table."

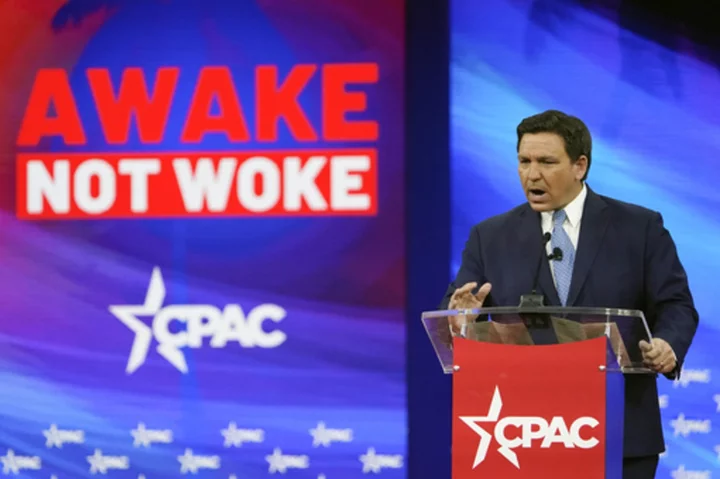

The film bounces between family pleas and legal contexts, but it lands definitively on the inherent, limiting problem of the criminal justice system, which prioritizes additional funding towards punitive pathways and a "hard on crime" ethos while casting alternative measures to the wayside.

Humans versus cases

The beginning of the film highlights this dichotomy through a brief historical rundown, chronicling the legal precedent that established the right to an attorney, and thus the creation of public defender offices, as well as the rise of the Los Angeles County's own department, which is the oldest and largest of its kind in the country.

While the criminal justice system and incarceration rates grew rapidly around the U.S., public defender offices stagnated and funding waned. In fact, public defenders have struggled over poor funding and major case loads for so long that the haggard, overburdened state-appointed attorney is its own fictional trope.

In 2015, Los Angeles County decided it needed a change, and thus began a five-year path towards a giant overhaul of its systems, resulting in a brand new way to manage and store client case data to expedite their legal defense and centralize their interactions with the courts.

For more Social Good stories in your inbox, sign up for Mashable's Top Stories newsletter today.

Mohammed Al Rawi is the first-ever appointed chief information officer for the Los Angeles County Public Defender's office, despite it being nearly 110 years old. He's a veteran of public service and digital systems who was tasked upon his 2019 hiring to help implement and manage the newly created Client Case Management System (CCMS).

"Digital transformation tends to happen out of frustration," he told Mashable. "In order for me to bring a solution, I needed to reverse engineer the problem. If we try to fix a problem without understanding how we got here, we will just go back."

The problem, as both Kessler and Al Rawi explained, was that decades of court procedure had effectively dehumanized the Public Defender's Office and its work. Instead of an approach that focuses on and organizes around the individual, offices (and the system as a whole) organize based on antiquated, frequently decentralized, case file numbers. Humans are rendered a number, numbers get confused or lost, and both people and attorneys get lost in the matrix.

Credit: Breakwater Studios / Publicis SapientAl Rawi had to turn a case-centered environment into a people-centered one. "I have 160 million records that are case-centered, but I was recruited at an organization that represents people, not cases. Do I keep this status quo and continue to marginalize the people involved? Or do we really unfold the biggest paradox and understand why it was case-centric to begin with?"

Bringing an antiquated system into the light

Publicis Sapient won the 2015 bid to help fix the problem. "If you can associate all kinds of pieces of information about a person, you can then enable the public defenders to provide the best defense possible of that person," Kessler explained. Instead of an architect, he said, think of Publicis Sapient's work with Los Angeles County's Public Defender's Office as that of a general contractor, tasked with making the county department's dream home a reality.

Or, even more simply, think of the modernization effort like a group of kids at play. "A lot of those technologies you could consider to be Lego blocks," he said. "We get all the Lego blocks, and then we have to figure out how to build a specific building out of those Lego blocks."

The Lego structure that is the CCMS is a mansion of judicial information for public defenders across the county.

The CCMS was built from a variety of configurable platforms, primarily Salesforce and Amazon Web Services, although there's a lot more at play than just those. It uses data parsed from those millions of pieces of paper and half-digitized files to create robust profiles of individuals who have moved through the court system at various times in their lives, a human-in-the-loop process that involved creating new searchable attributes for clients and deleting numerous duplicate files that are created because of the case-number system. The system also collates court calendars and precinct information from around the county, Al Rawi explained, so attorneys can be notified of all relevant information for a client at any given time.

Even though we're still getting a 20th century paper form, we use AI to transform it into 21st century digital data.Because of the platforms used and its integration, the CCMS implementation didn't require any new software or hardware, and the learning curve is relatively flat — huge in the world of government offices. While most government agencies relied on creating housed systems like these from scratch, new digital, cloud-based technologies are bypassing antiquated systems.

"That's what was shown in the film," Kessler said. "Noah was able to assemble all these different pieces of information that he might otherwise not have access to so that he could provide his defense for Johnny."

Al Rawi and the county's IT department, as well as fervent attorney supporters, have spent the last three years since the CCMS deployment facilitating department adoption and working on continued improvements. "We are the only party that tells the story of the human in the court; everyone else tells the story of the mistake they made."

In addition to the simplified, human-centered interface, the system also makes use of AI machine learning to help public defenders quickly search and parse through huge case files, including providing transcripts of video evidence and facial recognition — similar to its controversial use by police investigators and prosecutors.

"I believe we are among the first, if not the first, to use AI to decarcerate, not incarcerate — to help prove the innocence of the accused," Al Rawi explained, alluding to the technology's anti-punitive, pro-restorative justice intent. "Even though we're still getting a 20th century paper form, we use AI to transform it into 21st century digital data."

SEE ALSO: Netflix documentary ‘Victim/Suspect’ digs into systemic scrutiny of sexual assault survivorsLos Angeles County as a global model

Al Rawi wants Los Angeles County to be a leading example for other offices in their efforts to modernize and in the path to reducing collateral contact with the criminal justice system. The barrier isn't technology, it's a desire for change and statewide politics.

Supporting Reyes' case, and Cox's public defender efforts, was a widespread criminal justice rehab underway in California. "We're in a very special political phase in Los Angeles," Al Rawi notes of the county's path to modernize the office. "We have a phenomenal Board of Supervisors, all women, and they have been very, very proactive and progressive in addressing the toughest and the hardest issues, including justice reform and the criminal legal system as a whole."

In addition to 2019 diversion laws for mental health cases and parents and caregivers charged with a misdemeanor or a nonserious, nonviolent felony, California Gov. Gavin Newsom launched a new system of courts that specifically handle mental health cases, known as Community Assistance, Recovery, and Empowerment (CARE) courts, which are set to be implemented this year. The 2021 California Racial Justice Act prohibits criminal conviction based on race, ethnicity, or national origin, a move to correct the racial disparities of the American judicial system.

Al Rawi sees this system as offering a quantitative example of an ineffectual system in tandem with government policies. "Public defenders can tell you how biased the criminal legal system is for days. They can tell you stories, but now they can do it in a quantitative way. Our attorneys are taking cases with data to show historically how unfair it is when it's broken down by race. It's become such a powerful tool to make cases at the bench level, with the judge, to help our clients."

Forgiving Johnny doesn't get into all of this context in its 20-minute running time, but it prompts viewers to think about the legal system a little deeper than most are used to.

"At its core, it's storytelling," Kessler says of the case study documentaries coming out of Impact Films initiative and Proudfoot's collaboration. "Storytelling is what unites us as human beings. As part of the same species, we can tell each other stories to enable us to act in a certain way in the future... Bees can only get together and make a hive. Humans can get together and tell each other stories to do something different in the future."

While so many Americans are resigned to the many exasperating ways people can fall through the system, the film's producers and main voice ask if a digital safety net might be able to save them. And through a tale of one family and one attorney's attempt to use the judicial system for healing instead of punishment, it lends a human face to the cry for change.

Forgiving Johnny is available to stream via Publicis Sapient's website and on all TIME platforms.