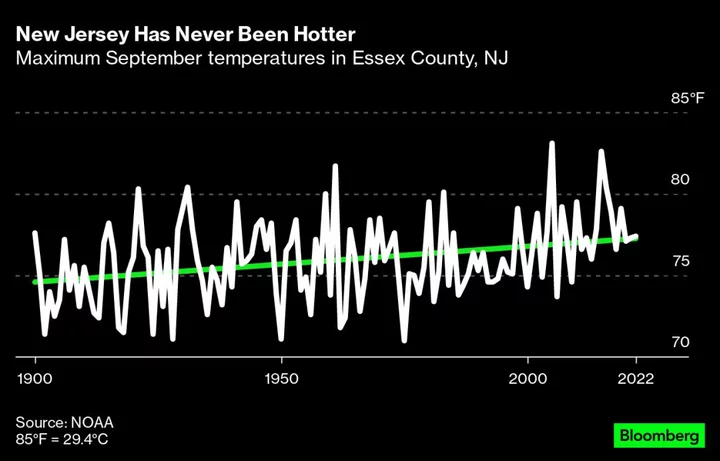

Bank of England rate-setter Swati Dhingra warned that consumers should prepare for more food price spikes in the future as climate change and geopolitical tensions cause shocks.

Dhingra said that Britain relies on imports to produce 80% of its food, a higher dependency than other countries and much higher than estimates by the UK government.

“Given that we’re going to be possibly — and I can’t be certain about this — possibly seeing more such kinds of food price hikes, primarily coming from the geopolitics as well as climate change, I think we need to have a food preparedness program in place,” she said Tuesday at a panel discussion hosted by the Festival of Economics in Bristol.

The remarks lay bare the UK’s exposure to global supply shocks and add to concerns of a return to more volatile prices. It also suggests difficulty for BOE policy makers in setting the course for interest rates and reining in inflation that remains more than triple the 2% target.

UK food price inflation soared to its highest level in decades earlier this year as the war in Ukraine disrupted the supply of grains and farmers were hit by a surge in their costs, including fuel, feed and fertilizer. While the increases in grocery bills have eased, food inflation in the UK is still stuck in double digits.

Dhingra, a trade expert, said the UK’s reliance on imported food is “pretty high” compared to other major economies, and as high as 80% when considering inputs to food producers, such as ingredients and fuel. That suggests a much higher dependency on imports than government estimates that suggest around half of the food consumed in Britain is from imports.

“We’ve got to at some point really have a big societal conversation about the fact that many of our prices, not just in food but more broadly, are not set in the UK, they are set abroad,” she said.

Dhingra is one of the most dovish rate-setters at the BOE and was voting to end interest rate rises long before the nine-member Monetary Policy Committee decided to pause the hiking cycle in September.

The BOE said in its November monetary policy report that it expects further declines in food price growth to be one of the key drivers of lower inflation in the near term.

It predicted that food inflation will fall to single digits in the final quarter of 2023 and to around 5% in the first three months of next year. The BOE said it would take time for an easing in input costs in the food sector to feed through to prices on the shelves for consumers.

New figures due on Wednesday are expected to show that overall inflation fell sharply to 4.7% in October from 6.7% the previous month.