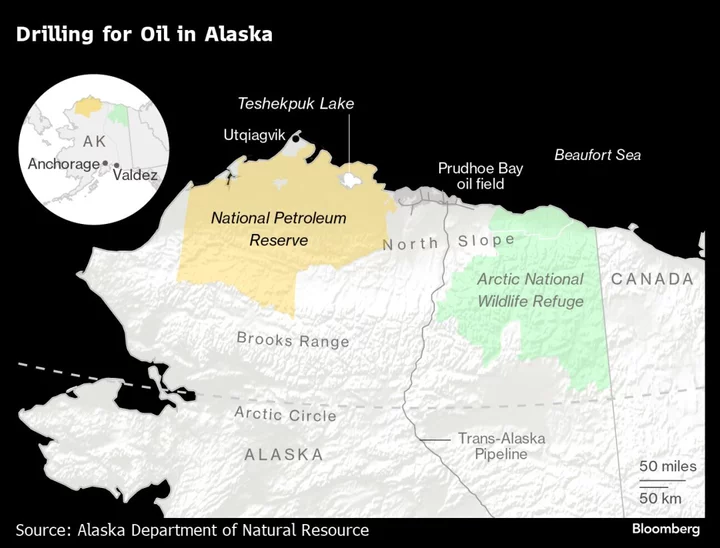

A century after the US set aside a broad swath of northwest Alaska to be used as an emergency oil supply, the Biden administration is pursuing changes that could make it impossible to harvest crude from new leases in the 23 million-acre site.

The proposal for managing the National Petroleum Reserve-Alaska has alarmed oil industry advocates who say it would thwart development in a crude-rich region the size of Indiana. Alaska’s congressional delegation said the Biden administration is “suddenly and dramatically reinterpreting the law so that it can treat 13.1 million acres” of the reserve “as de facto federal wilderness.” And a top ConocoPhillips Co. executive says the changes stoke uncertainty about future oil projects and infrastructure across the region.

The proposal “would discourage investment on the North Slope by adding more layers of permitting requirements and restrictions, even for existing leases,” Erec Isaacson, the president of ConocoPhillips Alaska, said in an interview Thursday.

The Interior Department argues a new framework is needed to balance development with environmental protections given the approach was last substantially updated in the early 1980s. It seeks to “raise the bar for development” in response to rapid warming in the region and accelerating degradation of the permafrost, the agency says.

Environmental advocates applaud the approach, saying it is necessary to meet climate goals as well as conserve habitat for caribou, grizzly bears and migratory birds.

“That they’re making it harder to develop petroleum in a petroleum reserve indicates they understand the seriousness of climate change” and the need to enlist public lands as part of the solution, said Athan Manuel, director of the Sierra Club’s Lands Protection Program. “We can’t be so laissez-faire about how we regulate oil and gas operations moving forward.”

Red More: Biden to Cancel Arctic Oil Drilling Rights Sold by Trump

The proposal would expand safeguards for current and future “special areas” across the preserve. At least once every five years, federal regulators would be required to designate new special areas for maximum protection because of their wildlife, scenic or other values. And those designations could not be undone unless the special values — the wildlife, for instance — disappeared.

Oil industry concern has focused on provisions directing the government to presume oil leasing and infrastructure development “should not be permitted” even in areas of the reserve open for that activity unless there is specific information clearly demonstrating the work can be done with “no or minimal adverse effects” on the habitat.

The proposed rule upsets a current balance between energy production and conservation, ConocoPhillips’ Isaacson said. It “presumes permits shouldn’t be issued for energy production except in circumstances that are undefined and might be so narrow they even impact viability.”

The Interior Department has said the measure won’t affect “currently authorized oil and gas operations.” Isaacson said that includes his company’s mammoth 600-million-barrel Willow oil project, as approved earlier this year. Other companies with projects or holdings in the reserve include Spain’s Repsol SA and Oil Search Ltd.

Alaska’s congressional delegation successfully petitioned the administration to extend time for the public to weigh in on what it called “sweeping changes” that will affect local communities, existing leases, future leases and the infrastructure needed to connect tiny oil fields to the Trans-Alaska Pipeline System.

The lawmakers — Democratic Representative Mary Peltola and Republican Senators Lisa Murkowski and Dan Sullivan — said their initial review shows the plan “would result in unprecedented restrictions on a variety of activities across” the reserve. The proposal, they said, “fails to reflect the balance between oil and gas development and the protection of ecological and cultural values that is called for” in law.

Author: Jennifer A. Dlouhy